His manner is restrained and his attiring is neat. The picture registers as a portrait—most of his body is in view—but what is a portrait without a face? Regardless, there are other details to be seen besides his positioned body, including a scattering of weed on loose sand, an overhang of branches along a concrete fence, and, most instructively, a pink-hued fabric thrown over a background stand. This stand covers just the area the young man is sitting, almost perfectly aligned with the low bench. It is clear that there was enough room to picture him from the front or side. What’s unclear is why the photographer chose this patch of earth to make a man obscure.

— Emmanuel Iduma

“Photography is an opportunity to learn about others in an intimate and vulnerable way.”

This photo was taken in Maiduguri, Borno state, in northeast Nigeria, in 2021. I was commissioned by the New York Times to make portraits of Boko Haram fighters who had just surrendered and were housed by the government at a camp on the outskirts of the city.

The editors at the Times wanted silhouette portraits but I thought that silhouettes were overused in this kind of portraiture that concealed identity. I wanted to try something different. I told the editors I preferred to set up a backdrop outside using fabrics that are commonly worn in that region and make the portraits. I worried the editors won’t like this idea, but I was happy they were on board, and I had to hit the ground running to do some research on the fabrics by going to the market and speaking to fabric sellers and people on the street. Then I met with the former Boko Haram members to hear their stories. They liked the idea as well, although some of them didn’t mind their identity being shown. But of course, I had to protect their identity. As much as the story was very heavy, we had light moments when we shared a couple of jokes in the process of chatting.

I chose this particular photo because of the young man’s story which I found quite poignant. He shared the story of how he was misled and lost his teenage years to become a mid-level commander and one of Boko Haram’s key assassins.

At some moment while listening to him calmly share his role and how he assassinated and slaughtered people, I would want to punch and strangle him. Another moment I felt like giving him a hug to tell him I’m sorry he lost his teenage years and was misled to join Boko Haram. As much as he wanted redemption, he was aware of the consequences of his past and saw it as fate. He said he will continue to seek forgiveness within. And he wished he could personally meet the families of the people he killed and seek their forgiveness.

My encounter with him and other members reminded me of this quote by Bell Hooks: “Forgiveness and compassion are always linked: how do we hold people accountable for wrongdoing and yet at the same time remain in touch with their humanity enough to believe in their capacity to be transformed?”

For me, photography is an opportunity to learn about others in an intimate and vulnerable way. By genuinely learning about someone else, you learn about yourself. Empathy is the beginning of understanding. I’m a curious person by nature so I apply that to my approach. Everyone has a story and is dealing with some form of internal or external conflict; and so, a lot of my work relates to people dealing with some sort of conflict. I want people who are interested in my work to look at my photos and think about what’s happening in the frame and question their humanity and privilege.

— Tom Saater

About Tom Saater

Tom Saater is a Documentary photographer/Photojournalist, Documentary film maker, audio story producer, Researcher from Nigeria. His work has been exhibited internationally, including in the Venice Biennale, University of Oxford, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art Denmark, and as part of Everyday Africa traveling exhibitions across the world. He is a member and contributor to the photography collective Everyday Africa. More of his work can be found on his website.

Last Week — “Stranger Tourist,” by Fares Zaitoon

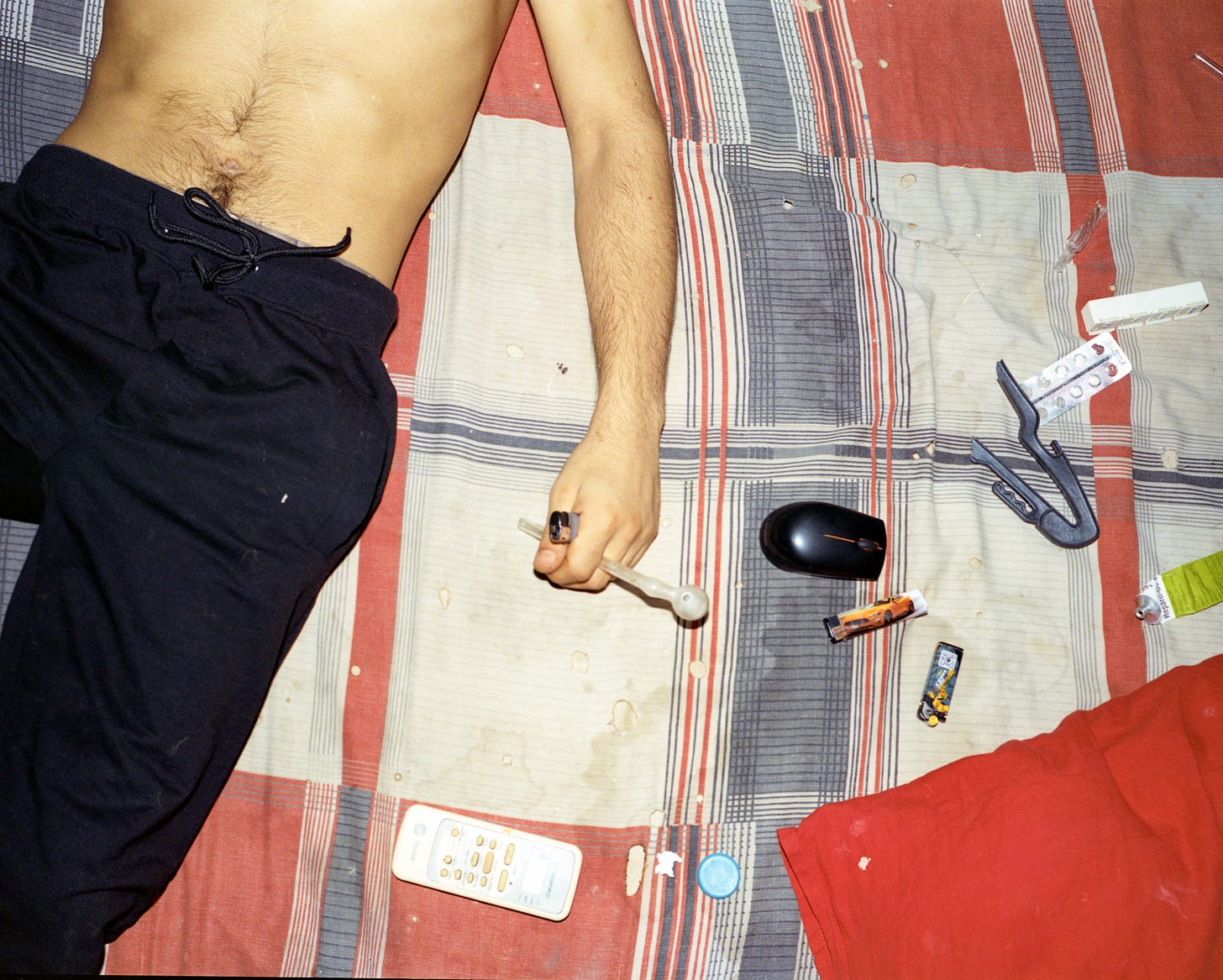

I was a drug addict myself for 10 years and I recovered 7 years ago. Momo was my friend when I was an addict. We were a big group that took drugs together heavily; two died, one lost his mind, I recovered, and Momo is now in his worst stage of addiction especially when he got into the world of crystal meth.

SUPPORT TENDER PHOTO

This is the 82nd edition of this publication, which also read on web (best for viewing images), and via the Substack iOS/Android apps.

Every Wednesday I feature one photograph and the photographer who took it: you’d read a short caption from me, and a statement from the photographer. Every Saturday, I publish a series of commentaries in response to photographs previously featured on the newsletter. My hope is to engage with early to mid-career African photographers, and to create a platform in which photographers lead the cataloguing and criticism of their work.

Photographers can now submit their work for consideration.

Thank you for reading. If this newsletter was shared with you, consider subscribing, or forward to a friend. Please whitelist the newsletter to ensure you never miss it.

I love the idea of shooting the portrait in that style rather than the usual silhouette. A1 for Tom

Such a cool format to learn more about the story behind the photo!