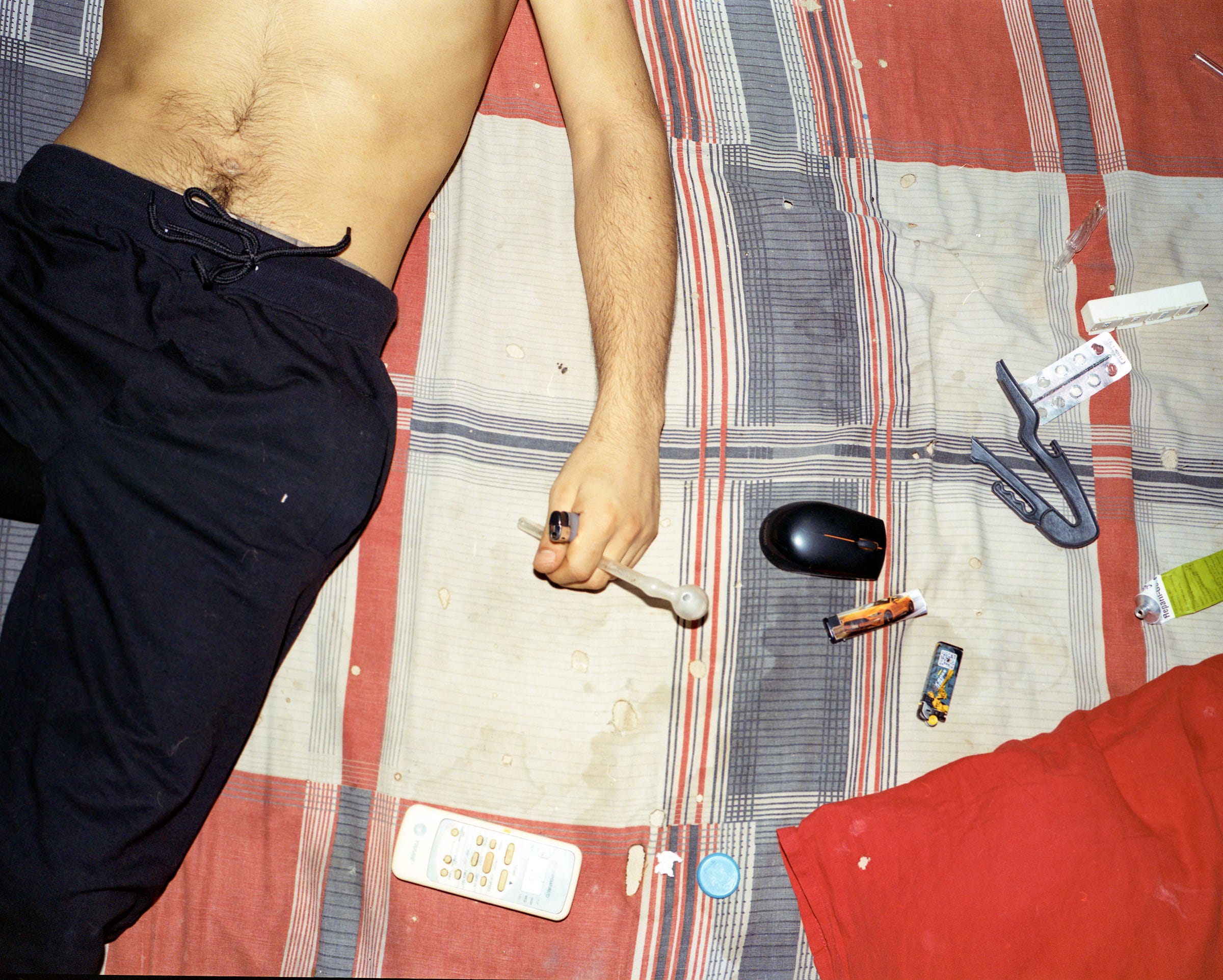

On my screen, the photograph opens as a perfect square. It shows a still life of items on a soiled spread of cloth. These items are random both in their placement and in their diversity: a remote control next to a plastic cap, the half of a hanger beside a medicine packet, a mouse close to a lighter. The unerect body beside this curious arrangement is angled along the edge of the frame, showing an arm, most of the torso, and three-quarters of a leg. And despite what is visible in the picture, I wish to see what is not on view. A face, for instance.

— Emmanuel Iduma

“Reflecting on a relationship with my protagonists is more significant than documenting a particular moment.”

The photograph was captured towards the conclusion of my project on a friendship with Momo tested by drug addiction. Momo had been unable to sleep due to extended crystal meth use, spanning around 6 or 7 days—though the exact duration eludes my memory. Eventually, he managed to find rest on the same mattress that had remained unchanged for years. Significantly, the presence of the mattress holds a certain potency for me, as it encapsulates Momo's life more comprehensively than I ever could. It serves as a symbolic description of his journey.

I was a drug addict myself for 10 years and I recovered 7 years ago. Momo was my friend when I was an addict. We were a big group that took drugs together heavily; two died, one lost his mind, I recovered, and Momo is now in his worst stage of addiction especially when he got into the world of crystal meth.

I distanced from him when I recovered because I was afraid being around him would usher me to a relapse. I have a personal relationship and background with both addiction and Momo. And despite all the ethical concerns I had about doing this project about a non-sober addict, even If he was my friend, I still believed that my background with both drugs and Momo safely helped me claim that I was the best to do the project.

Getting into Momo’s life, I was always questioning the life he had inside his black-walled room. I was fortunate to gain his generous trust. I believe this is because of many things we went through when I was an addict. There were many situations where he was in trouble back then and I helped him out. Also, the fact that he knows that I don’t come from an “otherness” gaze.

When we started the project I asked him if he was sure that he consented and was okay with me photographing his private world. And he said: “I wouldn’t allow myself to be your rat lab, but I trust you and I am comforted.”

Using photography, I create worlds that explore my reality from the one that I live in and have difficulty accepting. In my experience with drug addiction, I strived to look within, draw inspiration, and find a way to express complexity. I did this by documenting experiences adjacent to my own, which are often on the margins of society's discourses. I used myself as the starting point for a broader discussion. My approach is more focused on asking questions than providing answers. Reflecting on a relationship with my protagonists is more significant than documenting a particular moment.

— Fares Zaitoon

About Fares Zaitoon

Fare Zaiton is a self-taught photographer and visual artist born and raised in Cairo, Egypt. His his work has been featured in Vice Arabia, CNN Arabic, Mada Masr, Daily News, and Cairo Scene, British Journal of Photography, Spiegel magazine. He was nominated for the CAP Prize 2020 for Contemporary African Photography. In 2021, he earned a scholarship to the Danish School of Media and Journalism, and in 2022 received a scholarship to H-S Hannover University. See more of his work on his website, and Instagram.

Last Week — “Two Brothers at Usuma Lake,” by Victor Adewale

I am always looking for something that surprises me or that sparks a feeling. I think that photography is such a powerful tool to make people feel. When people feel, they want to take action. Today I don't use a zoom lens because it seems to exclude me from the process of image-making, and gives all the power to the camera. I don't want to just take a photo; I also want to share in the moment as much as I can.

SUPPORT TENDER PHOTO

This is the 81st edition of this publication, which also read on web (best for viewing images), and via the Substack iOS/Android apps.

Every Wednesday I feature one photograph and the photographer who took it: you’d read a short caption from me, and a statement from the photographer. Every Saturday, I publish a series of commentaries in response to photographs previously featured on the newsletter. My hope is to engage with early to mid-career African photographers, and to create a platform in which photographers lead the cataloguing and criticism of their work.

Photographers can now submit their work for consideration.

Thank you for reading. If this newsletter was shared with you, consider subscribing, or forward to a friend. Please whitelist the newsletter to ensure you never miss it.

There is within the story Fares tells and the title a lesson. When you escape a bad place and either have to visit it again or you meet someone from that place, your first instinct is flight, look away, don't engage, keep contact brief. However, that is a rookie move, open your eyes, look clearly, engage, for in doing so you might help someone else escape or keep yourself safe.