Light Fall

Photographs by Sehin Tewabe, Hashim Nasr, and moshood, previously featured on Tender Photo.

The degree to which a camera absorbs light is the extent to which a photograph is legible. Yet, as we see from the following images, the passing of light can be the raw material of a photograph as much as a subject depicted in it.

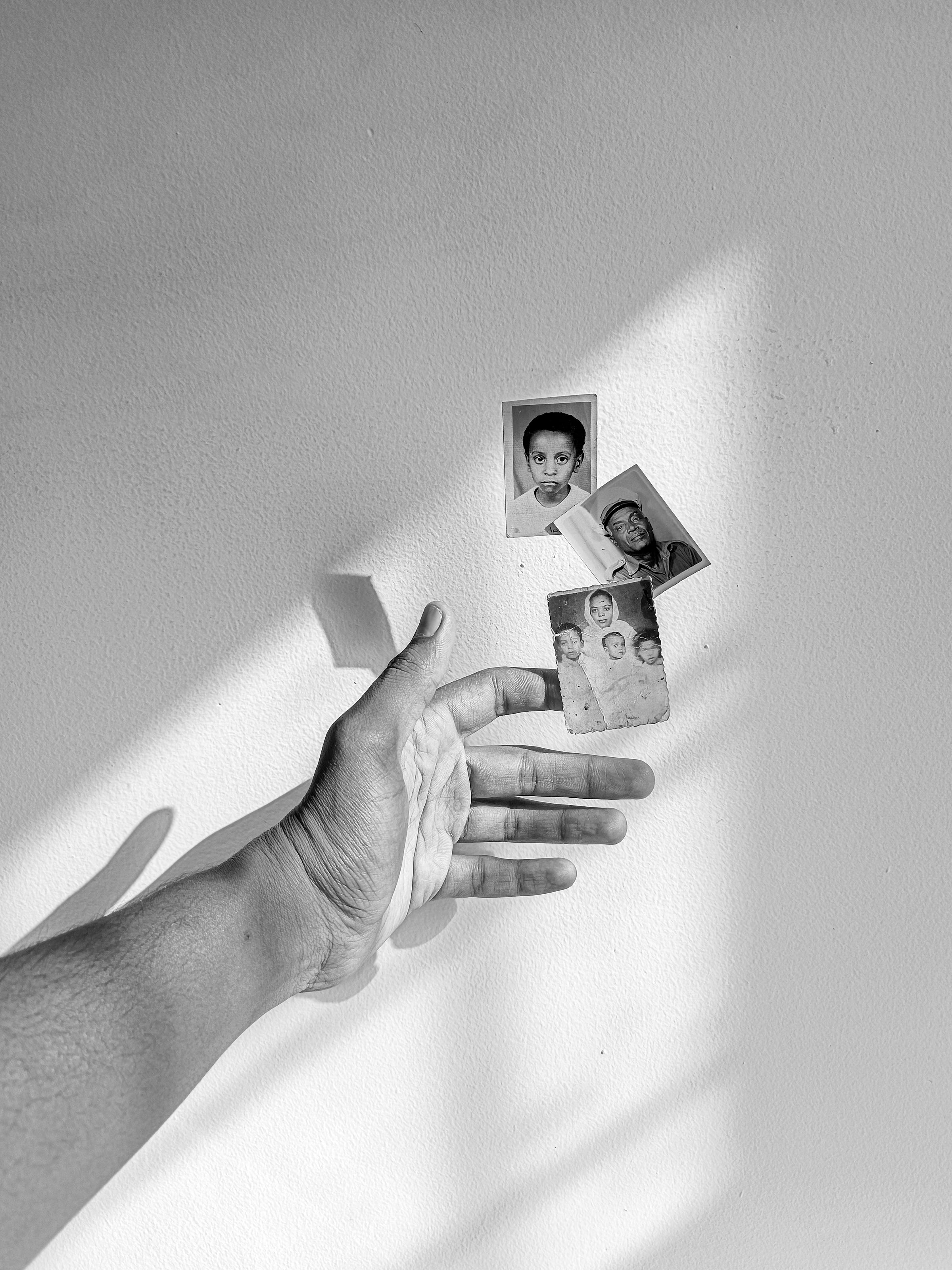

In Sehin Tewabe’s photograph, a neat, large trail of light puts two men in focus. In Hashim Nasr’s photograph of a hand, a polygon of light has formed at the corner of the room, so perfect in its serendipity it seems like an opening to show small, precious photographs. And in moshood’s picturing of a “slow Sunday” in Accra, there’s a clear line separating light and shadow, shade from heat.

Tewabe’s aptly titled photo is one of her favorites, and, as she writes, “stands out due to its exceptional composition, perfect timing, and the remarkable way lighting and shadows framed my subjects.” I agree with her assessment mainly for what she pinpoints about the conditions necessary to take the kind of photograph she did. “Perfect timing.” She was on her way to work, and saw two similarly dressed men standing above a heap of stones. There’s the shadow of a head in the middle of the frame, likely hers, facing the scene. It’s this silhouetted hint of an onlooker that puts the interplay of light and shadow at the heart of her photograph—spotlighting men, who, with their heads bent, deal with private matters.

“In the photograph,” writes Nasr, “I am holding portraits of myself at the age of six (1996), of my grandfather when he was serving in the police (early fifties), and of my grandmother, dad and two uncles when they came to settle in Sudan in 1967.” With this contextualization in mind, we might come to understand why, even with the minimal background, the photograph seems crowded. We see both the hand and the photographs, sharpened and centralized by the slice of light.

Hence, to capture light in fleeting form is a practice of attention. It’s what moshood discovered in his walks around the Mokola area of Accra. For three consecutive Sundays, he looked for relevant scenes, positioned himself, and “pressed the shutter.” After a while, he realized that a number of the Makola photographs contained shadows, “trailing me all the way from my house, keeping me company.”

These shadows are, to me, stand-ins for the cool of a day. “The frigid surface holds you down, as though by some gravitational incantation: your body is transfixed, still and even small gestures are seized from wandering,” is how Anakwa Dwamena puts it in his response to another photo from the same series by moshood. As such the man who slouches in the corner has clearly embraced the moment, sure in his repose, easy in his bearing. •••

This is the #12 (and final) edition of CONCORDANCE, a series of micro-essays in response to sequences of photographs previously featured on the newsletter. These notes, inspired by CORRESPONDENCES, points to affinities in style, mood, or theme between the tendered photos.

TENDER PHOTO is a bi-weekly newsletter on African photography, published Wednesdays and Saturdays. See the archive for more features and commentaries on early to mid-career photographers, or submit your work. If this newsletter was shared with you, consider subscribing, or forward to a friend. Please whitelist the newsletter to ensure you never miss it.