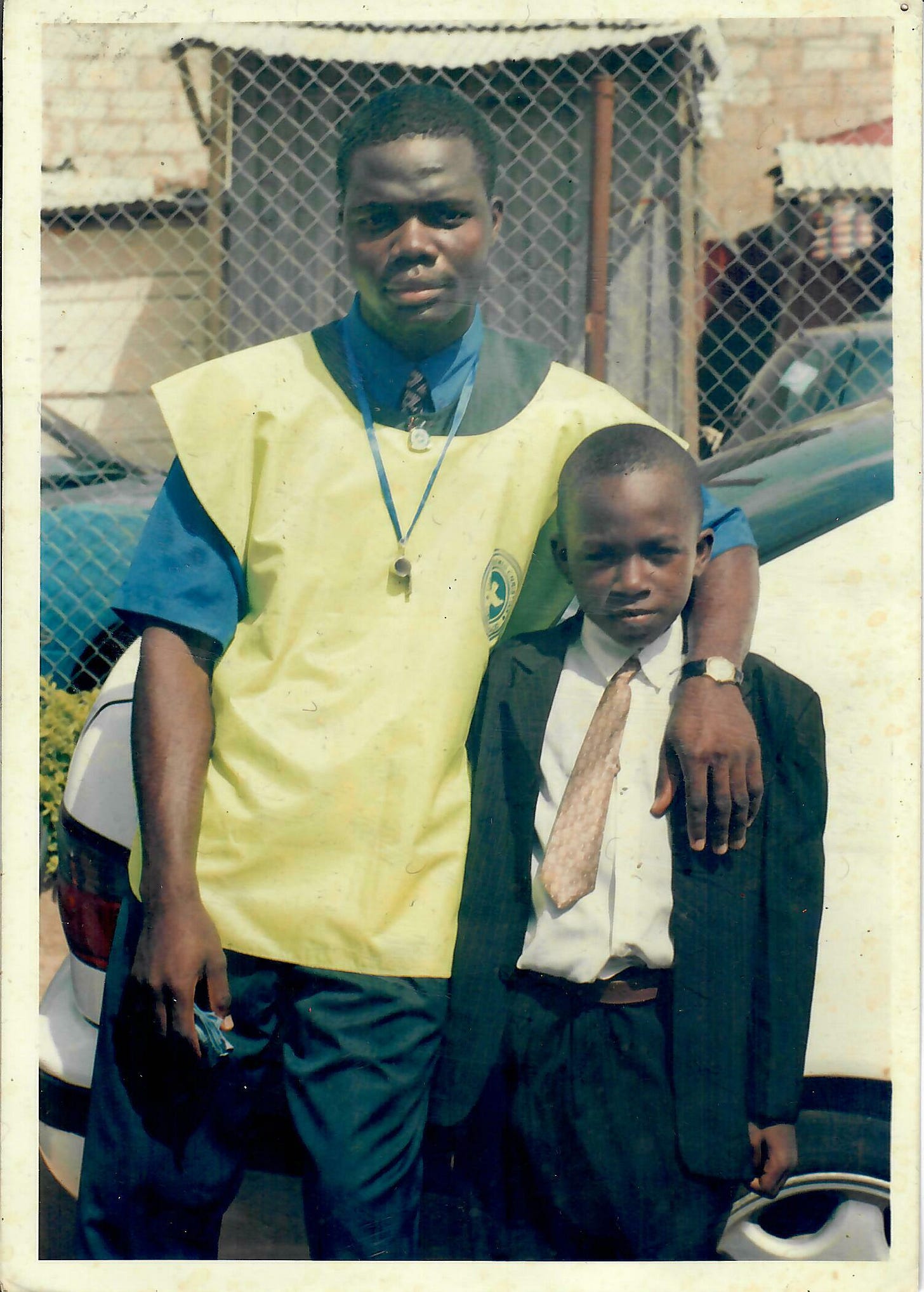

In this photograph of myself and an uncle, I am reminded of the tranquil state of the world as I saw it then on Sundays, my body—or was it my soul— having been lightened by the Word, by the welter of words I have consumed at Sunday School. And in the photograph of two brothers on a boat by Victor Adewale, on first sight I am struck by the placidity. Such silence! And still, though the calm of the waters is evidence enough of peace, because the two men are on opposite ends as in a seesaw, its revelation to me is that of a world ever-changing, ever-in-motion.

Yet, I am inspired by the correspondence between the two photographs. In both, there are two people united by an activity, an action, or even an act. In the former photograph, the pause and the pose—perhaps at the urging of the photographer—once again asserts photography’s exaltation of the moment into a monument; we are even made to stand still as statues. If in the latter photograph no one has struck a pose, there is still an evident rest and repose.

All the same, though the form of the family album is far from a piece of furniture, its place in the house seems unalterable, wherever that might be. Compared to the easy entry of mobile photo galleries and its seemingly seamless scroll—or is it stroll—from ancient history to recent past, the photo album bearing the abrasions of age will not be so casually turned and then tossed.

I realize now, why in my house the heaviest object might be the photo album. It is heavy with the consideration of its creator. It was meant to be both monument and memento, it was supposed to offer the opportunity for time travel even while it occasioned the retelling of yesterday’s stories.

If that Sunday was like any growing up, what I wanted from the Word was to let me in and to also take me on excursions into hitherto unknown parts of the world. The photo album, as the picture of myself and my uncle reminds me, is far from the saintly perfection of the Scriptures—cut and pasted from a clutter of events, they are not even whole, not to talk of holy—but they are perfect for what they are: a repository of photographs that are both time machine and theatre, both port and portal. ¶

About the Contributor

Olaniyi Omiwale was born in Lagos, Nigeria. His writing has appeared in Saraba Magazine and in A Long House, among other publications. He currently lives in Abuja. Find him on Instagram.

This is the #8 edition of KINDRED, a series on TENDER PHOTO. Each contributor selects a photograph from their family or personal album, pairs it with another photograph from the Tender Photo archive, and writes a short reflection on why they have selected both photographs. The idea is to find an analogy between two photographs that might be similar or dissimilar in composition, but connected to an experience, emotion, or idea.

TENDER PHOTO is a bi-weekly newsletter on African photography, published Wednesdays and Fridays. See the archive for more features and commentaries on early to mid-career photographers, or submit your work. If this newsletter was shared with you, consider subscribing, or forward to a friend. Please whitelist the newsletter to ensure you never miss it.