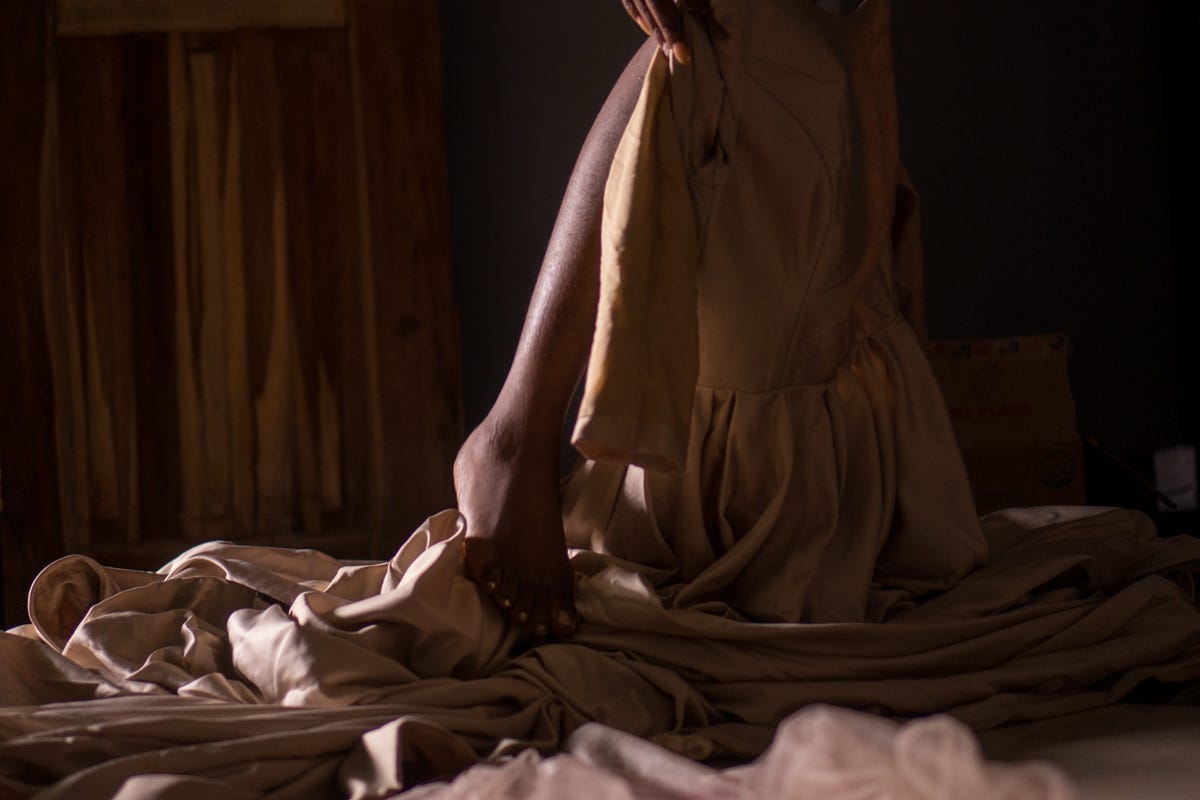

It is impossible to tell whether they stand in a room or in the open, and whether the woman’s hands are lit by a fire or a headlamp. Yet, “impossible to tell” isn’t the exact phrasing to describe what is seen or what isn’t—darkness is not the absence of light as much as the limit of the eye. How many women are there? How many girls? Who among them hasn’t held up her hands? Given my unknowing, to focus on the face of the woman in a red hijab—the bulge of her cheekbones, the angles of her face—is to accept that, as one of our most acclaimed writers once wrote, “darkness is not empty.” In this darkness I observe a relay of prayers.

Nelly Ating: “I consider myself an insider in every project, meaning I have to be personally exposed to a problem to be able to understand it.”

This photograph was taken in Yola, Adamawa State, Nigeria.

In 2017, I was invited by a colleague at the American University of Nigeria, Yola, to visit a small community of internally displaced persons in Yokossala, near the border of Cameroon. These IDPs had formed a society based on their shared interest as herders and farmers while resisting living in camps. Within a short time, I developed a friendship and bond with the community members. Upon seeing their living condition, especially the lack of potable water, I decided to go beyond just documenting their lives but crowdfunding online to support the community with potable water. The project took almost a year, but the community had clean water with the support of Editi Effiong and Joseph Oladimeji. They were heavily involved in seeing the project to the end. The night I captured this image, the women prayed for all the virtual strangers who donated to their cause.

I hold this picture close to my heart. It showed me why Nigerians find hope in religion as a society. I look back and think about Yokossala as part of the many intersections of the impact of Boko Haram. For some communities, they became united. For others, the insurgency deepened religious tensions.

I visited Michika, a local government in Adamawa, in 2016, shortly after it was recaptured by the military. The IDPs had just also returned home, but not without fear of a reprisal attack. The tension between the Christians and Muslims had worsened. While in Yokossala, I saw a force of unity against evil. As I continuously interrogate my documentation of the aftermath of the Boko Haram insurgency between 2014 and 2020, I find something beyond resilience: fortitude. Creating a shared community was also a force of resistance towards the very reason Boko Haram thrived. Together as a collective, they aimed for self-sufficiency without relying on the government, thereby preserving their dignity.

My approach to photography keeps evolving. The more I opened myself up for further learning and introspection, I realised there were ethics I needed to abide by. I borrowed the ethics of journalism when I had to tell difficult stories.

My approach to photography has always been research driven. I consider myself an insider in every project, meaning I have to be personally exposed to a problem to be able to understand it. I lived in Adamawa for almost a decade, and during that time I also heard bomb blasts and visited sites of an attack. I have travelled far out of Adamawa to understand the extremity of insurgencies. The coverage I provided have become archival materials which I am now hoarding.

Today, I approach photography as a historical record and evidentiary material. Quite polysemic and allowed for varied interpretation or re-imagination. It is why I am venturing into creative practices like collages or a conceptual genre of storytelling.

I know some scholars frown upon the use of decolonisation. I know we are saturated by the posturing of some who claim to decolonise art, literature, history, or photography. Bad news for those who may be tired, but the act of decolonisation is what we are still experiencing with the burgeoning photographers from Africa telling indigenous stories. We may not like it, but it is the truth. Again, this is my truth. It is relative to yours. Photography has enabled me to see and deconstruct my gaze as a Nigerian and how I view other African countries. It is from photography that I understood the Black Gaze existed. And also the non-neutrality of the camera when we go to rural communities to tell stories. Mind you, these stories are essential but it is necessary to understand the social power dynamics and cultural relativity when approaching these communities. Photography is not objective but subjective.

I am swamped daily with photographs that subvert my understanding and challenge my bias of the world, from joy to rage, beauty to death, grief to noise, unconventional to conventional and so on. It is why I do not take it lightly when people think photographs are not harmless. They can be used as references, evidence or objects of the past, of which we must come to acknowledge the power of such signification. The work that each photographer from Africa is currently performing is decolonisation. It is a continuous effort, one that shifted from a nationalistic tone to portraying Africa's agency. We need to louden that effort, which is the impact African visual culture can have.

Two other photographs by Nelly Ating

About Nelly Ating

Nelly Ating is a photojournalist who focuses on questions of identity, activism, education, extremism, and migration. Her photographic work documenting the rise of Boko Haram terrorism between 2014 and 2020 in Northeast Nigeria highlighted the intersections of extremism and the aftermath of conflict. Ating has presented her work in academic and non-academic settings in Africa, Europe, and America. She is currently a PhD student at Cardiff University, researching human rights discourse through photography. She is a member of Women Photograph and The Journal Collective. See more of her work on Instagram.

Last Week — Nengi Nelson

I like my photography to feel candid and in the moment. I am very intentional with the surrounding or environment of the image but I allow the subjects to express how they want to be represented, especially in documentary style photographs. I find the most candid moments when I allow them to be as they choose. I explore other kinds of photography that allow me the space to interfere directly with the outcome so I find the balance in that.

Read more: Support System

Support Tender Photo

This is the 38th edition of this publication. The newsletter can also read on web (best for viewing images), and via the Substack iOS/Android apps. Every week I feature one photograph and the photographer who took it: you’d read a short caption from me, and a statement from the photographer. My goal is to set up conversations with the work of early to mid-career African photographers. If this newsletter was shared with you, consider subscribing, and if you have already subscribed, please forward to a friend who loves photography.

I am grateful that Tender Photo was recently featured in Feature Shoot and FlakPhoto, two Substack newsletters/communities I follow with keen regard as well as recommend.

Just incredible.

Kudos for taking us there!

“They can be used as references, evidence or objects of the past, of which we must come to acknowledge the power of such signification.” YES! Thought-provoking read. Thanks!