“Photography is a way of questioning the world and creating a dialogue about it.”

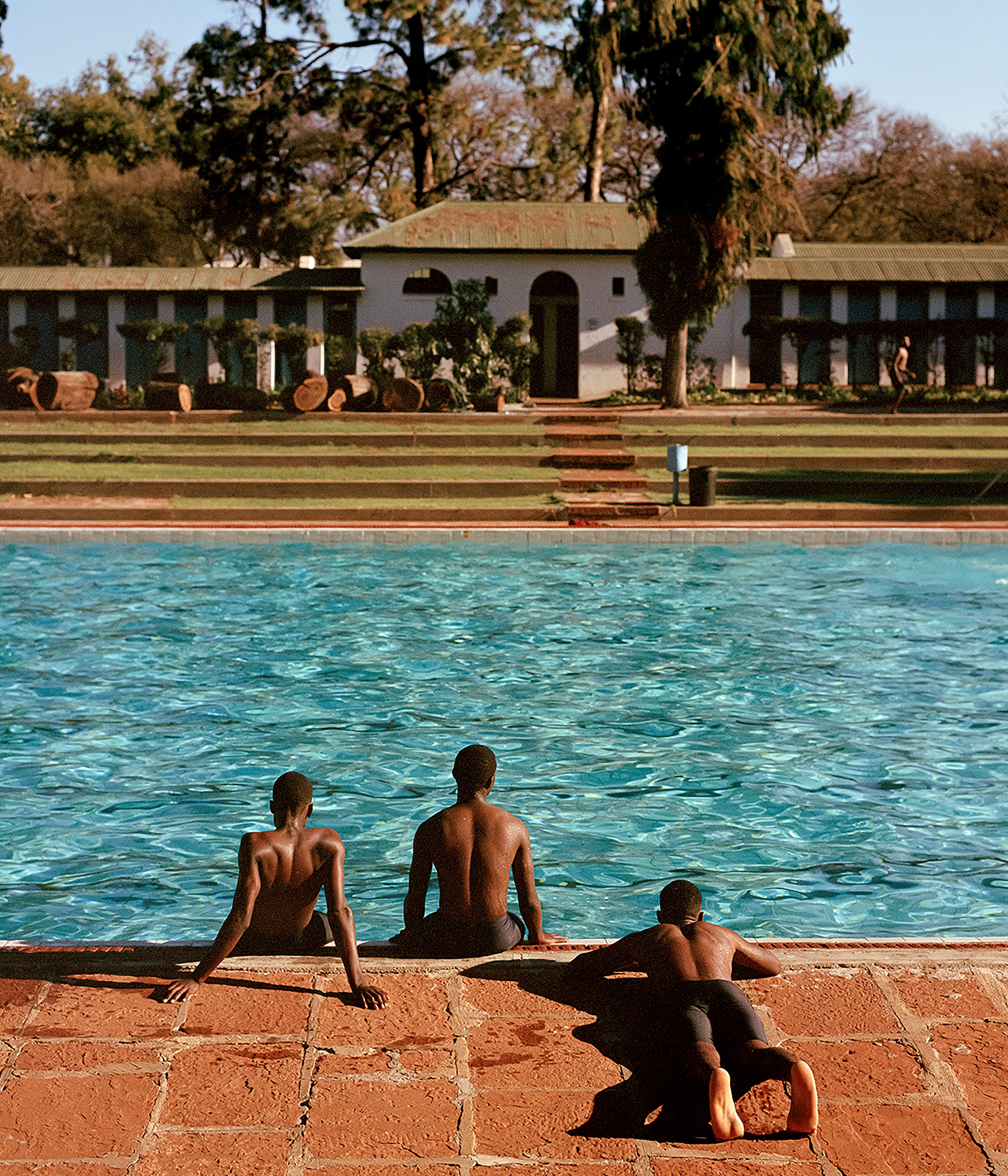

This photograph was made at Borrow Street Municipality Swimming Pool in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe.

I made this photograph whilst working on a long-term project called “Born in Africa: Death Unknown,” which was an exploration of white Zimbabwean identity that used the symbolism of swimming pools, once deemed the pinnacle of the Rhodesian Dream and the highlight of Rhodesian lifestyle, to navigate the complex post-colonial landscape. Having a swimming pool was something to aspire to and inadvertently it became—and, in many ways, still is—a symbol of privilege. While many things have changed—the decline of the British Empire, Zimbabwean independence, the emergence of a black middle class and the deterioration of the Zimbabwean economy—many of the mentalities associated with the heyday of the swimming pool have not.

So as part of my process I tried to visit and photograph as many private and public swimming pools across Zimbabwe with Borrow Street Municipal Swimming Pool in Bulawayo one of the best maintained and most accessible pools in Zimbabwe. Strangely enough, I was waiting for a clear frame of the swimming pool. It was the first week of August school holidays and despite it only just being the beginning of Spring and not particularly hot, the pool was surprisingly full. These three gentlemen had been swimming widths when they decided to take a break and warm up in the sun and everything just fell into place.

I wasn’t looking for this photograph, I wanted to make a completely different photograph of Borrow Street, so I guess what makes this photograph special to me is that it’s a personal reminder to be open to the unexpected, a reminder that sometimes what you’re looking for isn’t what you are going to find, and that is the fundamental joy and challenge, for me, of being a photographer. Beyond that, I think there is something special about the essence of youth, camaraderie and freedom that I feel is evident in this photograph.

Photographically I see my work as an examination of myself, of my upbringing, and of my white Zimbabwean culture which for large portions of my life I have been completely blind to. It is driven by my aim to unpack the colonial history of Zimbabwe whilst simultaneously locating my own position, past and present, within it. I think the notion of “home” is always romanticised, and it is no different for me. But I want my work to simultaneously reflect the beauty of home whilst attempting to confront my own belonging to it. I think it’s important to question the narratives of our history and our collective identity. I’m particularly motivated by creating new collective memories that represent a more honest relationship to the history of our country.

I think photography is impactful in a lot of ways: it is a way to collaborate, to communicate, to contribute to a visual history, to create a visual record of life, of things, of anything. Photography is a way of questioning the world and creating a dialogue about it. Personally, Photography has given me the immense privilege of experiencing the world whilst challenging me to make my own vision of it. It has granted me intimate access to people and places that have changed my life. It has allowed me to live and in many ways it has saved my life.

— Jono Terry

A miracle of composition

There are three bodies, facing a house with three sections. A miracle of composition. Between the boys and the house there is a pool, and a stretch of low steps. Also, the figure of another half-naked boy in the distance, turned away from the house and pool. The boys who face the pool hold their bodies with a relaxation that points either to fatigue or contemplation. Better the latter.

— Emmanuel Iduma

About Jono Terry

Jono Terry (born Zimbabwe, 1987), is a London-based documentary photographer whose work is primarily focused on post-colonial Africa. His long-term photographic projects aim to both unpack and confront colonial history whilst offering insights into its continued legacy on contemporary African society. As a grandson of British immigrants to Rhodesia, he is strongly motivated by creating a dialogue about the past in order to decolonize the present. Find out more about his work on his website, and through Instagram. Other features of his work can be read at Wul Magazine, and Musee Magazine.

Last Week: Nneka Iwunna Ezemezue

It was difficult getting access to widows who were willing to share their stories. Somehow I met Theresa in a Catholic church. I had gone there to pray. She was willing to share her story. She took me to her house and we talked. She told me her story of widowhood and the photo she’s holding was something she treasured.

Read more: Theresa

Support Tender Photo

This is the 48th edition of this publication. The newsletter can also read on web (best for viewing images), and via the Substack iOS/Android apps. Every week I feature one photograph and the photographer who took it: you’d read a statement from the photographer, and a short caption from me. My goal is to support early to mid-career African photographers by engaging with their work. If this newsletter was shared with you, consider subscribing, or forward to a friend. Please whitelist the newsletter to ensure you never miss it.

Something about saying 'this was photograph was made' and not 'this photograph was taken' excites and concerns me. If i compare it like i always do to poetry writing. A poem that was written seems hurried, snapped, quickly. Whereas, a poem that was made seems deliberate, edited, cleaned to sepia. I wondered if the pool was edited.

This is my favorite newsletter thank you for sharing the beauty and joy!