If you were to mark four rectangular lines on the white cloth, you’d notice that the four people pictured are sitting or standing equidistant from each other. This detail reveals, best of all, how specifically they have posed, and how resolute they are to show themselves in true form. It is a notice-me mood, but I equally sense a so-what. As though self-judgement is the most effective of assessments.

— Emmanuel Iduma

“This portrait speaks of the traces of history.”

This photograph was taken in Putten, The Netherlands. It’s a small farmer’s town in one of the nature provinces in the country.

I have ideas about Dutch and South African culture that are like pieces of a puzzle that slowly come together in my head. My brothers and I styled our clothes, shoes and hair before we went outside. A lot of thought went into this process as we combined things that inspired us. My brothers decided on the t-shirts of Tupac and Biggie, two of the biggest rappers in North America who were friends and then foes from the East and West coast. This history also feeds the photograph. There are a lot of parallels between their culture and South African culture, including gangsterism, oppression and poverty. When Alexander bought these t-shirts, he came home with the Aaliyah one too, which I decided to wear. To stay within the African American and Black culture, Benjamin wore the Lebron James Cleveland Cavaliers 2016 outfit, the year they became the NBA champions.

Sometimes the visual I have in my head does not match reality. That is what makes it a difficult process, because of the need to pivot sometimes. My brothers are also not always in the mood to be portrayed. I directed the composition of the portrait before it was taken by a friend of my older brother Alexander.

I am studying visual Anthropology, and my research centres around the first forms of photography in South Africa by Euro-American anthropologists in which people of colour were transformed into objects, used to justify colonialism and apartheid. Just as people of colour were half-naked in front of a white cloth to be so-called objectively examined, I wanted to do a complete 180. My brothers and I have the freedom to create a portrait that speaks to how we want to visualise our sense of belonging, our idea of what identity can be.

The love of our white Dutch father and our South African coloured mother is the foundation of our family. It is one of the millions of examples showing that people want to blend, integrate, and unify, no matter the colour of their skin. Ethnic minorities are still a topic of discussion in the Netherlands. Some politicians are inspired by Donald Trump’s America First policy, and say that it is time to put the Dutch people first. But who is a real Dutch person? My brothers were born here, but do their dark curls, durag and Tupac t-shirt make them non-Dutch? I’ve spent over 22 years in this country, and I have a Dutch passport. What does that make me? This portrait speaks of the traces of history and is an ode to being a person of colour.

Photography is my medium to deal with questions I have and grapple with my mixed heritage in a somewhat playful, respectful, confrontational and accepting manner. It is also my tool to heal because photography grounds me in a project that helped me go through mental health issues. I’d been experiencing panic attacks since I started the series “Mixedness is my Mythology” and lost my confidence, motivation and sense of self. My body didn’t feel like it was mine and the level of painful symptoms and insecurity made me feel like I was drowning. However, thinking about inspiration and putting the puzzle pieces together for this project has helped me heal. Photography is so much more than an apparatus to create images.

I fell in love with the work of J. D. 'Okhai Ojeikere years ago. He portrayed female hairstyles and made them monumental statements of African culture. Portraying women from the back to focus on their hair may feel simple, but 'Okhai Ojeikere turned hair into an elegant moment of beauty. Deana Lawson’s work does the same for me. Every time I see her work I want to go to South Africa and portray people of colour in their community. Photography, therefore, does not only inspire, it opens my eyes to see how others perceive and portray their community.

— Farren van Wyk

About Farren van Wyk

Farren van Wyk (1993) is a South African and Dutch photographer. She received her BA degree in Photography (2016) and is finishing her Masters’s Degree in Visual Anthropology. For her, the centuries of colonisation, the slave trade and the Dutch participation in apartheid are deeply ingrained in the country of her birth. This historical and somewhat troubling relationship between these two countries that she calls home sparks a lot of questions that she tries to answer within her photography projects. More on her work via her website, and Instagram. You can also read interviews with her here, and here (Dutch).

Last Week — Kay Kwabia

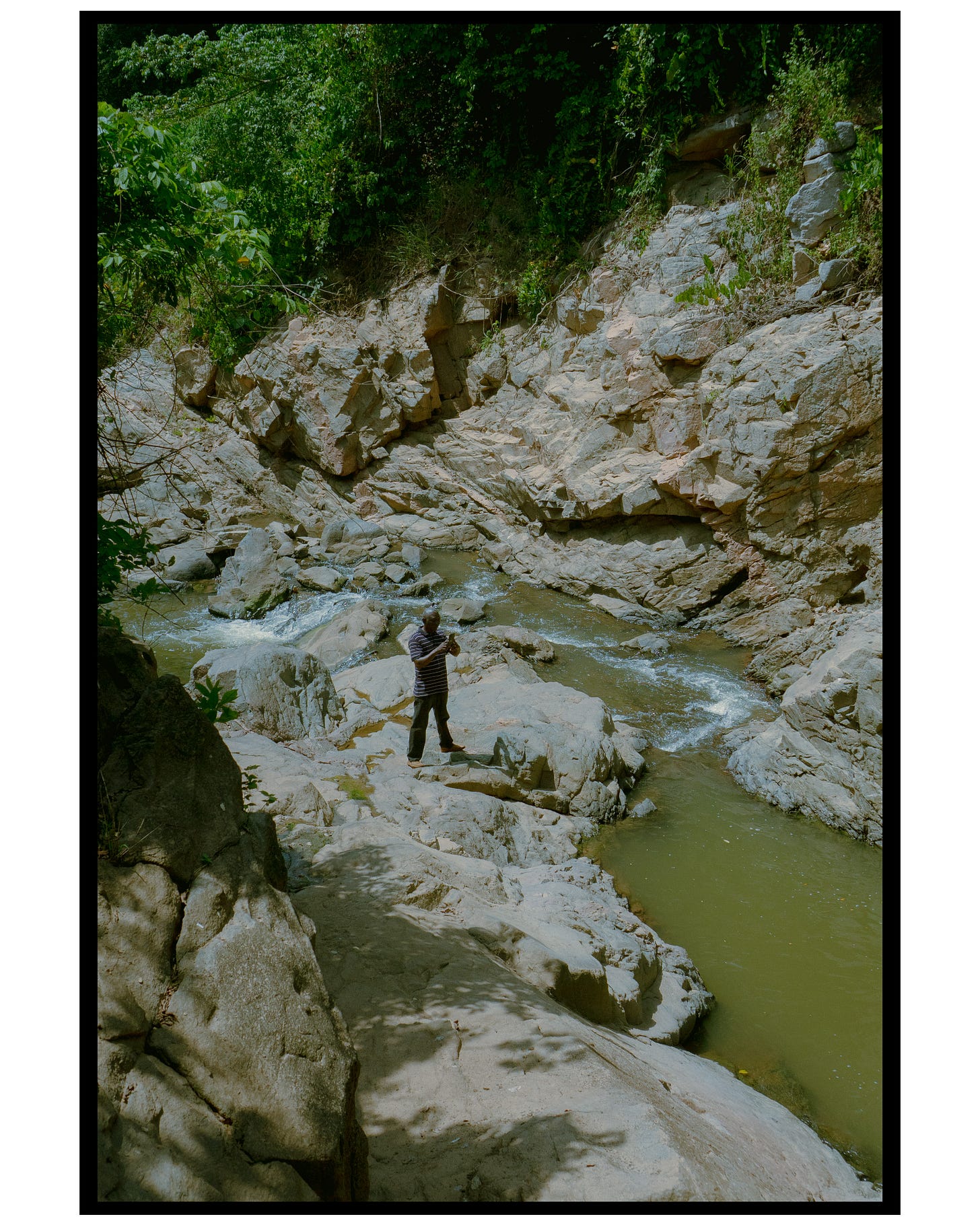

My first priority when documenting anything is the aesthetic value. Color, light and form has always fascinated me and through photography I am able to express how I perceive them. No matter the subject I may be documenting, I place emphasis on how to make their colors and form look interesting and highlight how light gives them character.

Read More: Know Your Backyard

Support Tender Photo

This is the 50th edition of this publication. The newsletter can also read on web (best for viewing images), and via the Substack iOS/Android apps. Every week I feature one photograph and the photographer who took it: you’d read a short caption from me, and a statement from the photographer. My goal is to support early to mid-career African photographers by engaging with their work. If this newsletter was shared with you, consider subscribing, or forward to a friend. Please whitelist the newsletter to ensure you never miss it.

There are several ways to write about a moment. These days I am interested in the portrait method. Writing like a camera panning slowly. Direction does not matter. There are so many names in this photograph - Aaliyah, Biggie, Tupac, Michael Jordan, Nike, Adidas. And the defiant look on their faces is a homage to a culture that refuses to be hidden.