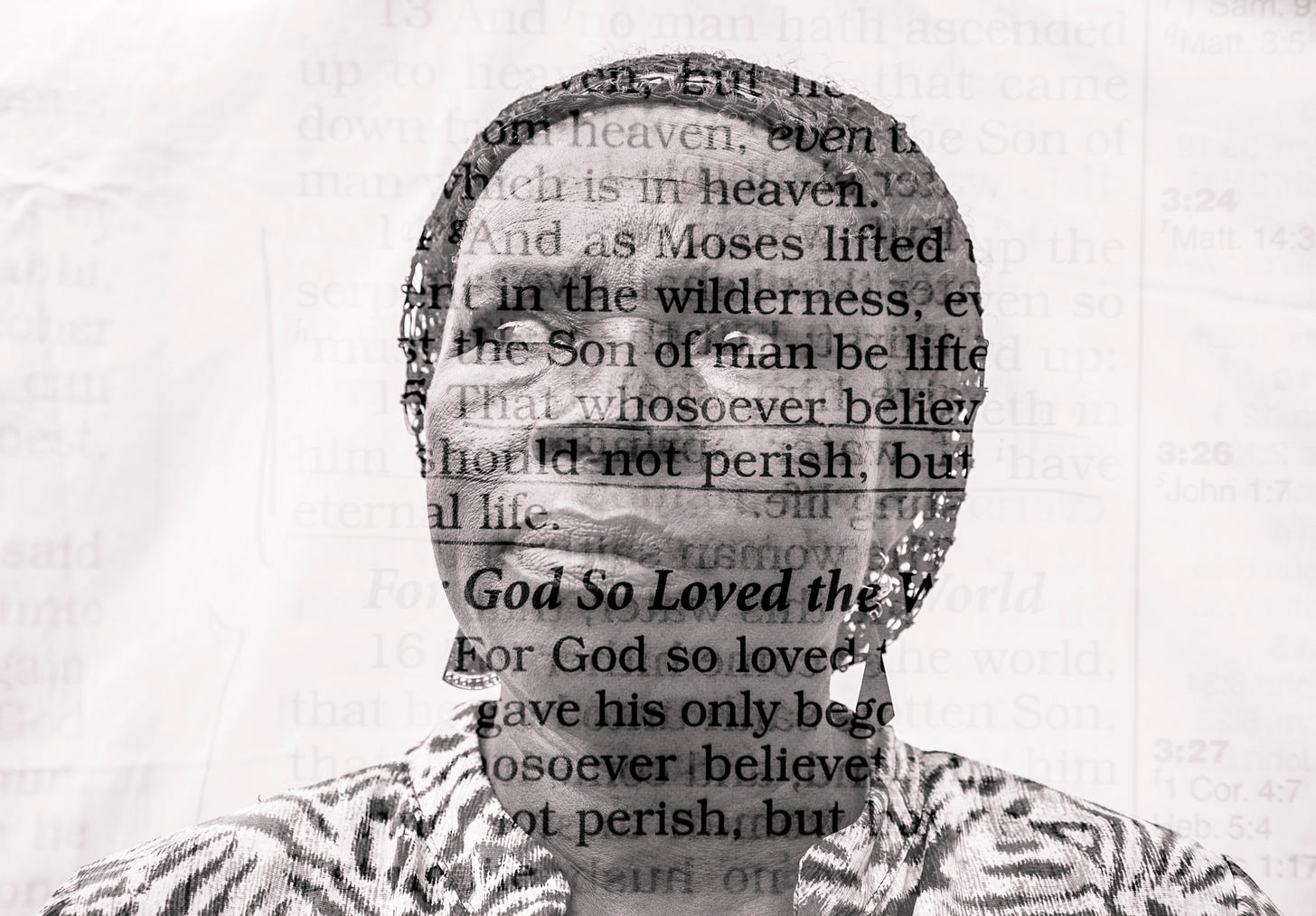

Here are two views of a man in a floral-patterned ankara dress. On the left, he is pictured from the side, his face halved. Like this the view is intimate, baring a tiny blotch below his eye, and the scattering of inch-long hair across his cheek. On the right, where he sits on the arm of a chair with a raised leg, he turns in a frontal pose. The background against which he is framed is as sanguine as his dress, making his poise a counterpoint to the riot of colours. That he is presented as both full-length and close-up, and not either, is clearest in the assurance of his demeanour. Looking away, looking at: we know him twice. And which of us, wanting to be seen, do not wish for a similar doubling, to be both body and character?

Etinosa Yvonne: “I approach photography with care.”

The photograph was taken in a studio in Abuja. The image is part of a series of images I began creating in 2020 as part of a project called Unboxed which explores perceptions of masculinity as it relates to outward appearance among Nigerian men. The project looks at limitations that society puts on men which limits them from expressing themselves, and masculinity as it relates to identity.

The name of the man in this photo is Dada Javis. He’s a nail technician, and a beautician. He also takes care of women’s hair. I went to get my nails done in a salon and we got talking. I told him I was working on a project and it would be lovely to have him in the studio. And he agreed. This was on a Saturday, and by Sunday he was in the studio.

We tried to make plans but because we had a discussion on Saturday and he came to the studio on Sunday, I couldn’t make out time to do it the way I normally do it, to take my time to plan his outfit. But I made sure I went to the studio with a variety of backdrops, and thankfully I went with safe colours – black, brown, navy blue. He walked into the studio and I thought, “It’s good I have a brown backdrop!”

I try to ease people into the session; when they walk in, I let them catch their breath, I talk. There’s food if they want to eat. Once I ask if they’re ready and they say they are, we start.

I really love the Dada Javis image. One of the things I love about the image is his performance. Now, his performance was of him installing beards. We had a conversation about his favorite body part and he said he loves everything about his face. He told me about how he normally would install beards. Right there in the studio he did that. It was just magical to see him do that. I had never seen a man with artificial beards. And so if you look at the image on the left, you’ll see a close-up shot of him with beards. But if you look closely at the image on the right, you’ll see a full portrait of him, there are no beards, just little facial hair.

I liked the transformation that occurred in the studio and I love how he was open. I don’t force the men to do what they don’t want to do. And, it was lovely to see him open up and say, “This is part of my grooming routine, I actually don’t have beards, but I put beards that last up to six months on my face.”

I’ll say I approach photography with care. With everything I do there is genuine interest, there is discipline, and there is balance. If I am going to take on an assignment or work on a project, I have to be interested in the subject matter. Every project I’ve done, or I’m working on, or will work on, it’s because I have a genuine interest, or genuine connection.

For me, photography is not just to explore themes related to social injustice. It is also for me to express myself. Whether it is me looking at a serious subject matter, or expressing myself artistically, there has to be that connection to the subject matter.

As a photojournalist or a documentary photographer, I am a timekeeper. My work is not just taking pictures, but preserving history, recording the now. A new generation is coming. When we’re no longer here, this is what they will look at and understand what happened at so-and-so time. We are visual record keepers.

Photography has changed my life. It has helped me become a traveler. Without photography, I don’t think I’ll have traveled as much as I have around Nigeria. Using this medium, I don’t just consider myself a photographer, but also a visual researcher. It has made me unlearn and learn a lot about Nigeria, about humanity. It’s a very powerful tool.

Two other photographs by Etinosa Yvonne

For each week’s feature, I send 3 photographs to the photographer, and ask them to respond to one. Here are the 2 other photographs I selected from Etinosa’s portfolio and sent to her. What do you think about any of them? You can respond as a comment below.

What to Read

This week, I’m browsing through The Photographic Collective, an online platform that “aims to highlight the work produced by photographers and visual artists based in and from Africa, especially those who are not currently represented by a gallery.” Etinosa Yvonne is one of the featured artists. See, in particular, the conversations with the artists.

And, I stumbled on this enlightening 2013 article in Africa is a Country: The story of how the most famous portrait of a young Chinua Achebe was taken. “The photograph reads as a cautionary tale,” writes Raoul J. Granqvist.

Thank you for reading and sharing this feature on Etinosa Yvonne. You can see more of her work on Instagram or on her website. Every week I feature one photograph and the photographer who took it. You’ll read a short caption from me, and a statement from the photographer. My goal is to set up conversations with the work of early to mid-career African photographers. You can support the newsletter by asking someone—or 10 people!—to subscribe.

There’s so much tenderness in the stories and the photograph. There’s care and there’s truth ❣️