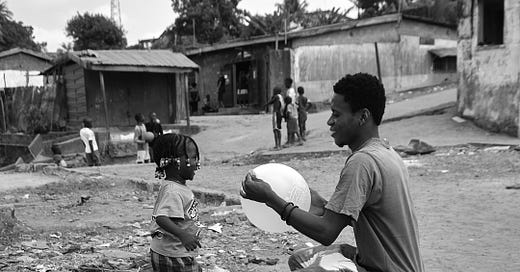

Many African photographers have sought to indicate an ‘everyday’ element in their work. They aim to show nothing of the sensational, especially if the photographs are of places or people historically pictured in a stereotypical manner. Their everyday scenes focus on the usual rhythms of life, what might even be described as banal—such as the three elderly women in the middle of a game of Ludo in a photograph by Abdul Hamid Kanu, or a man crouching to hand his daughter a balloon. Perhaps it is best to describe these photos as highlights of inconsequential encounters that could have passed unrecorded.

Yet, photographers like Kanu often speak of a larger ethos in their documentary work. They wish to record such everyday scenes with the conscientiousness of archivists; the story of any people, they claim, is often an amalgam of ordinary moments and citizens, and photography is a tool of social history. This is an accurate estimation if only because most people in the pictures were often unknown to the photographer until the moment he asked for their picture.

If the photograph is any good—if it captures a remarkable gesture or action or demeanour—we might sense genuineness in a transitory encounter, and might feel, too, that a warmth of emotional truth is passed to us.

How such warmth is conveyed in a picture often has little to do with the technical attributes of a photograph, even though that sometimes helps. The enduring poignancy of what is generally referred to as street photography—photos taken with little fore-planning in a public space—is found in the simple fact that in everyday life, there is an unpredictable range of picturable moments to be found, and the photographer’s true skill is in deciding what ‘poetry,’ in Kanu’s parlance, to pluck from the flow.

Now the kindly gaze of the man with a fisherman hat is more illustrative of his geniality than if he were seen a moment earlier, in the middle of a row. And the plaintive expression on the boy’s face fixes him as contemplative, rather than in the middle of concerted play with his friends.

Kanu succeeds with these well-timed monochrome pictures because he is familiar with Freetown. The people he has photographed, even if they are meeting him for the first time, recognize a familiarity in his ease with them. This is why, in many instances, he keeps the background in the frame, showing a street sign or unpainted wall or kiosk, just so he might mark the picture as local.

— Emmanuel Iduma

Listen to Abdul Hamid Kanu describe his project

Abdul Hamid Kanu, a self-taught photographer, is deeply inspired by the beauty of everyday life and the power of storytelling. His work focuses on themes of home, belonging, and documenting daily lives and experiences to archive for the future. See more of Kanu’s work on Tender Photo.

TENDER PHOTO is a collaborative digital archive and publishing platform of contemporary African photography, edited by Emmanuel Iduma. Our aim is to use photography to engage with life on the African continent. We publish narratives about the people, places, and events pictured in photographs, contributing to nuanced and layered perceptions. Every Wednesday we feature a photograph, a short caption about it, and a statement from the photographer. Last year, we published commentaries or photo-essays in response to photographs previously featured on the newsletter, including CORRESPONDENCES, CONCORDANCE, KINDRED, INDEX, and AFFINITIES.

This is the fourth edition of a series dedicated to the 5 photographers featured in Process Projected, Amsterdam. Read last week’s feature on Thero Makepe.

Thank you for reading. If this newsletter was shared with you, consider subscribing, or forward to a friend. Please whitelist the newsletter to ensure you never miss it.

Wonderful photos!

The portraits are great! Thanks for sharing!